Recently we spent a week in agriculture-based communities in California’s Central Valley. This post is the beginning of a series on what we heard, learned, and were surprised and inspired by from the people we spoke with there. It was a reminder to us of the central principle of journalism: The emotional and informative power of things you didn’t know, until you showed up.

The Central Valley is an important, and under-covered, part of America. It is important in obvious, dramatic ways. The Central Valley represents roughly 1% of US farmland, yet produces as much as 25% (by value) of all US-grown food. It is at the center of long-standing debates about California’s water supply, about its immigration policy, about its economic inequalities, even about the routes for its High-Speed Rail system.

The Central Valley also has an outsized place in American cultural imagery. It’s been the setting for famed literary works, from Bret Hart through John Steinbeck to Joan Didion. Its landscape has been in movies, from East of Eden to American Graffiti to Ladybird (and the less well-known but excellent McFarland USA.) Demographically most of it is majority-Latino; environmentally it has more hazards than the rest of the state; economically it would be poorer overall even than Mississippi, if it were considered as a stand-alone unit. Its economic leadership is mainly Anglo. It is in the part of California that votes red.

Over the past dozen years, we have reported extensively from the biggest city in the Central Valley, Fresno, with a population of just over half a million. Fresno was the northern stop on our recent road trip, which started in Bakersfield.

This opening report will be based on the imagery of communities in the Valley: What you learn and feel, by being there. We’ll follow with reports about the communities, schools, work, higher education and skilled training, health and well-being of residents, and more.

If we told you simply that Lost Hills is a town in the agricultural Central Valley of California, you might move your mind’s eye to a the images familiar from news accounts, or novels and movies. Images of workers in citrus and nut groves, celebrations of quinceaneras and baptisms, trailer parks and small dwellings, some well-tended and some not, and everything blistering under relentless sun.

All those images still apply. But there is much more to the story of Lost Hills and other communities in the Central Valley, based on what we have recently seen.

During more than a decade of visiting towns across America for Our Towns, we would typically come across pockets of engagement and promise. At first we were surprised, but soon we began to look for and expect the signs. A riverwalk here, a mural project there, Main Street beautification, tree planting, a brewpub opening in a distressed part of town. One by one these could seem like small things, but we learned that they were often part of a broader possibility for renewal. In Fresno, renewal and revitalization on many fronts contributed to a positive, cheeky atittude.

In Lost Hills we found something on an entirely different scale of ambition and vision: the deliberate development of a town that would embrace the whole human experience. In sterile vocabulary, the words to apply would be housing, education, food, health, recreation, even culture and civic life. But in overall impression, the effect was much more vivid than that.

What appears to be happening there requires extraordinary place-based dedication by everyone involved, from the philanthropists who concentrated on this town, to the teachers, doctors, managers, and citizens who live it every day. Making this a nationwide model would be a challenge. But what they are achieving deserves notice.

The Scene in Lost Hills…

… Starting with a Bridge Across Many Divides.

On the edge of Lost Hills, the Wonderful Bridge (called colloquially the Wonder Bridge) is a stunning piece of architecture, a reptilian-like, bright grass-green pedestrian overpass spanning California’s east-west State Route 46, about 35 miles east of Cholame, where James Dean crashed his Porsche and lost his life in 1955. This stretch of SR 46 has been notorious for the hundreds of accidents, many dozens of them fatal, since then, and not even Lost Hills has been spared. The Wonder Bridge was the answer to another accident waiting to happen, as well as a bold statement of functional public art for the town.

The bridge was built in 2024, inspired and funded by Lynda and Stewart Resnick. The Resnicks are well-known figures in California and across the country, through the many companies they have founded or run. They own the Wonderful Company, a collection of familiar brands from POM Wonderful drinks (from pomegranates), Fiji Water, Teleflora, Wonderful Pistachios, Halo mandarins, almonds, and more.

The Resnicks’ business and social lives have been the subject of extensive journalistic coverage and civic debate. Our subject now is the part of their work that has received much less reportorial attention: Their commitment to the part of the state where many of their ‘Wonderful’ employees live and raise their families. And what they mean by the difference between “philanthropy”—ongoing involvement in the welfare of communities and people—versus “charity,” which is more simply giving alms. 1

Lost Hills has been the epicenter for their civic efforts. About half the households of Lost Hills (latest Census population 1863, or nearly 2500 counting nearby areas) are supported by someone who works at the Wonderful Company.

The bridge provides a safe crossing from homes or school on the south side of town to the new community center, park and playground, splash pad, and a soccer field on the north side. On the day we visited, the playground was teeming with 5 busloads of schoolkids from northern California, clearly enjoying a serious rest-and-play stop on their way to Disneyland.

Inside the community center, we met a group of Lost Hills women who stitch detailed, intricate bead work that is then fabricated onto 3-D forms. The women go by the nickname of the Haas Sisters; they work with the widely-acclaimed sculptors and artists, brothers Niki and Simon Haas, the so-named Haas Brothers. The collaborative project, advanced by Lynda Resnick, has brought the women a solid income, and a tangible product and pride for themselves and their community.

About a mile beyond the park, out Lost Hills Rd. is the Lost Hills Mobile Home Park, where some 100 trailers of varying degrees of livability are wedged together on small plots.

About 15 years ago, a young photographer named Sam Comen made his way to Lost Hills to capture the spirit of life there.

“Lost Hills was too much to ignore,” Sam Comen said a few years later, for a photo essay featured in the then must-read TIME magazine in 2013. Looking at his photographs of Lost Hills, you can’t help but think of depression-era Walker Evans or Dorothea Lange, although the vibrancy and color and modernity of Comen’s photos feature less solemnity and more vitality.

It was eerie to compare his photos with ours, as though the dozen years of time in between had stopped.

The local View of the National Housing Crisis.

The streets of Lost Hills could be a scene from America’s rural housing crisis; there is a collection of every kind of housing, but not enough of it. The worn-out trailer park. The gentrified doublewides downtown, nestled into yards with planted greenery and picket fences. Stand-alone bungalows. And new developments of well-showcased affordable housing, on smoothly-paved streets with sidewalks.

Almond Village, with 81 Affordable Housing rental units, townhouses and single family homes, was developed by Kern County’s Housing Authority and other county funds. The Wonderful company donated the land. Depending on Almond Village residents’ income and the trailer park’s plot and trailer sizes, rental prices between the two can be competitive—and the waiting list for spaces at Almond is long.

Lomas Lindas is another recent development. Wonderful Company also donated this land, and designed the houses, with big backyards, which were then locally built, and sold mainly to company employees. We toured a 3-bedroom 2-bath model with 3 local women; a mom, her two daughters, and a grandbaby, who lived down the street.

‘You Have My Children. I Have Full Trust in You.’

Innovative Schools, in Places Where they are most needed.

In two neighboring communities in Kern County—Lost Hills, with its population of around 1800, and the comparative metropolis of Delano, which was home to Cesar Chavez when he founded the National Farm Workers Association and now has a population around 50,000—are two K – 12 public charter schools. They are both known as Wonderful College Prep Academies (WCPA). The schools are open to all; some 40% percent of the students on the Lost Hills campus, and 11% on the Delano campus are from families affiliated with the Wonderful Company or the school. The Resnicks founded and have significantly contributed to these schools over the last 16 years.

We spent time on both campuses, and we’ll write about the academics and services for the students and their families later in detail. The offerings are vast, and include three healthy free meals each day, an onsite clinic and full health services for children at both campuses (and families at Lost Hills), social counseling, college counseling, and extensive academic and extracurricular activities, tutorials, mentoring, bus transportation, and so much more.

Showing Students ‘A Bigger world out there’

While in Lost Hills, we wanted to meet with school administrators who would have close eyes into the community, to get a sense of the lives and deep culture of the people there.

The Lost Hills school, not yet a decade old, is in a community that is well over a century old and home to generations of families, many of whom live in intergenerational households. Some arrived as part of the bracero program, which brought temporary farm laborers from Mexico through the 1960s. Others, to work in the oil fields. Others migrated from the US South and Plains states during the Dust Bowl of the 1930s, as portrayed in The Grapes of Wrath. It’s no surprise to hear the reasons why the more recent arrivals, first-generation immigrant families, are here. They are those who “chose to move here for a better life and better opportunity”, says Lupe Sanchez, the Executive Director of Programming and Partnerships at the school.

We met with Sanchez and Amanda Rollin, the Community Schools Manager, for WCPA. Their starting point as school leaders, Sanchez and Rollin told us, is to build trust and relationships. “Families, once they have the trust in you, they will say, you have my children and I have full trust in you,” says Sanchez.

It is probably essential that the personal stories of these administrators lock in with the personal stories of the region’s residents. We heard many times in the Central Valley—and elsewhere around the country—about the importance of role models proving you could leave the community and then even return to help. Such life patterns are powerful examples to families that have not experienced this themselves and often imagine a risk of “losing” their children to a different kind of world, far away from home.

Lupe Sanchez, who is Hispanic, grew up in this area. She spent 11 years studying and working in Davis CA, at the top of the Central Valley, and wanted to return to be closer to home.

The work in Lost Hills was important to her. She said, “I want to do my best to support kids, kids just like me, and give them those opportunities and show them that there’s a bigger world out there.”

Amanda Rollin, who is Black, grew up in a small town in Wyoming. She went to college at Fresno State and landed by serendipitous accident in a summer camp job in Lost Hills. She recalled her first impressions. “There’s literally nothing here. Why would people want to work in Lost Hills?” But then, she mused, “I just completely fell in love with the children…They were seriously so sweet and had an innocence to them… I saw some of the struggles they face and felt this desire to want to help them.” They reminded her of herself growing up, she said. Rollin has been in the area more than 14 years now, and has fallen in love with the community as well.

The administrators at Lost Hills described their mission, which has expanded beyond delivering academic instruction and meeting academic achievement. Now, particularly in the current, urgent political environment in this heavily immigrant area of California’s Central Valley, the mission includes: “How do we support our community? How do we protect our families? How do we protect our schools?”

What Helping Students Means, in practice

In tangible, practical terms, here are a few examples of how they meet these challenges.

—Organizational adjustments for the school: over the years, the school realized that attendance would drop during the wet season or long vacations. When work in the fields was slow, parents would return to their home countries. So, the school extended the winter break from 2 weeks to 3, so students wouldn’t miss school days. They also set up independent study programs for kids who would be absent even longer, to keep up with their work.

The adaptations worked for the school as well, as state funding is tied to the average daily attendance (ADA); more absences equal less funding. “This year might be different,” they said, anticipating that families may stay in Lost Hills, skipping the risks of travel to their home countries.

—Political adjustments: When we asked plainly if there were any families where parents had been deported, the answer was equally plain. “Yes, yes, oh yes, yes.” In one recent case, the mother in a family called the school to report that the father had gone to his required immigration appointment and “never came back.”

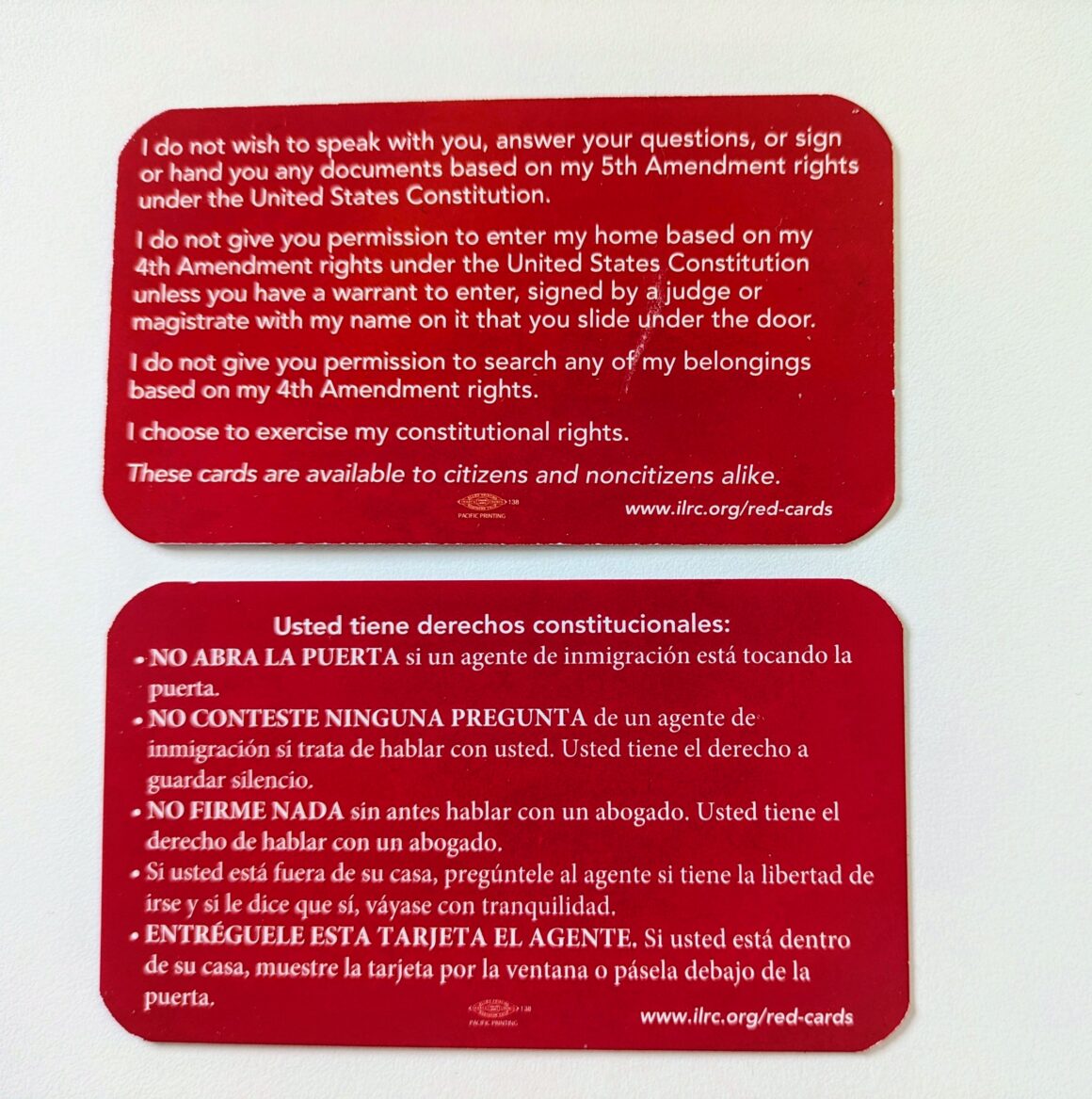

—Explicit guidelines help families plan ahead: Get passports and documentation in order; secure notarized letters identifying which relatives should care for children if parents go missing; learn about the Red Card.

A dividing line in Modern America: Families that need to have ‘the red card’

The Red Card is a small card, like an oversized business card or small playing card, printed in Spanish on one side, English on the other.

The drill on how to use it is simple. If an unknown person knocks on the door of your household, place the Red Card in the window. English side facing out, Spanish side facing you. We saw cards distributed in many places in the Central Valley.

When all was said and done, our conversations returned to the beginning, to the people and culture of Lost Hills. Lupe Sanchez underscored a point we heard in many other towns and regions – actually in just about everywhere except the handful of major US cities with proud, elite reputations. The question is: How do you reset the negative images of communities like Lost Hills, with the more representative stories of grit, discipline, devotion to family?

Sanchez’s answer lies in telling the stories of potential and resiliency and focus on the American Dream of people who live in communities like Lost Hills, “which is very much who we are as a country. And I think sometimes that gets lost in.. in everything…”

This is part of the story we want to tell in this series.

- We have come to know the Resnicks from forums and gatherings over the past 15 years, and have recently talked with them in person about their civic enterprises. In this series we’ll be reporting on what we heard and saw from people on the operating end of these efforts. ↩︎