A big theme in this election year is that other countries are swindling, out-negotiating, under-bidding, and generally beating the United States in the race for better jobs and companies. With a tougher stance, at least according to one candidate, the U.S. will be back in command.

On our return trip to tiny Eastport, Maine, whose scheme for survival I’d described in “The Little Town That Might” in 2014, my wife Deb and I were reminded of how surprisingly dense and unpredictable the tendrils of the global economy really are. We were also reminded how success in dealing with them requires a combination of planning based on what’s foreseeable, and adaptability to how things unforeseeably turn out.

That sounds obvious, but it’s always surprising to me to see how the ramifications show up place by place. Here’s a checklist of some ways in which a city that might seem as removed-from-it-all as any place in the country—it’s more than two hours by car from Bangor, Maine, four hours from Portland—is deeply enmeshed in worldwide trends.

For background: My Atlantic article about Eastport is here; Deb’s and my posts about it are here; the report we did with Marketplace radio is here; and while I’m at it, my Unified Field Theory on dealing with the global economy, from back in the 1990s, is here.

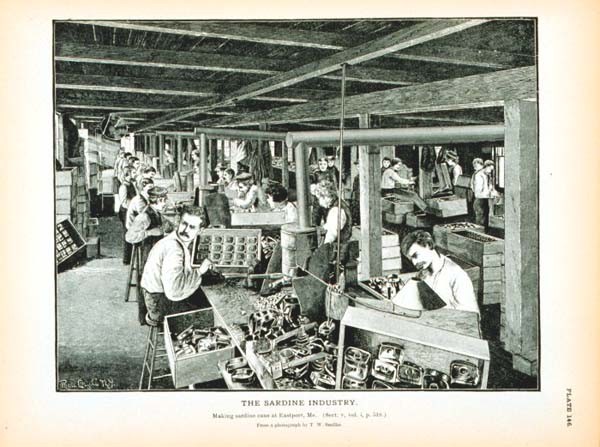

Because Eastport’s internal resources are so limited—some 1,300 people in one small place, a group that is on average poor and old even for Maine, which is poor and has the oldest population of all 50 states—by definition it has to look outward for opportunities. During its economic heyday roughly a century ago, it was connected to the world economy as one of the sardine-canning capitals of North America. Fishermen arrived with their catch; workers arrived from other parts of the country and the world to process the fish in the canning-houses, and to make the cans; packaged fish went to customers everywhere.

For environmental, economic, and other reasons, Eastport’s sardine industry went away. Eastport remained connected to the world largely through its proximity to Campobello Island. During the height of Campobello’s fame as summer home for the Roosevelt family, visitors could take a train from New York or Boston straight to Eastport, which was only a quick ferry ride across to the island. (The ferry is no more, nor is the rail line. Now it’s nearly an hour’s roundabout drive from Eastport to Campobello, circumventing the many bays and fjords in the area.)

When we first visited Eastport, the business and civic leaders we spoke with (and in a place like this, that means nearly everyone) stressed a new web of connections. The main ones were: a very deep-water port, that could serve markets in Europe and (as climate change made the Canadian arctic navigable) those in Asia as well; fisheries, with the area’s advantages in the farmed-salmon, lobster, and scallop industries; pulp and paper, from the surrounding vast Maine woods; clean energy, through the tidal-power projects I mentioned recently; regular vacation-style tourism plus eco-tourism, given the beauty of its coast and waters; and aspirational emergence as a center for arts and artists, on the model of other settings of remote beauty in New Mexico or Montana.

Those were the plans, which we heard from the likes of Chris Gardner, head of the port authority; Bob Peacock, an entrepreneur and pilot-boat captain who guides freighters and cruise ships into port; the influential “Women of the Commons,” whom you can read about here and who have worked to redevelop Eastport’s downtown; the members of the French family, responsible for the Quoddy Tidesnewspaper, the Tides Institute cultural center and art museum, and other ventures you’d expect in a city 10 times this large; and more. I’m listing them here partly in appreciation for their efforts but also as a one-stop-shopping source note for the developments I’ll mention below. We met these people three years ago and spoke with most of them again this past week.

What are their ventures, and what hath globalism wrought? Here are three illustrations:

1. Pregnant cows. For complex reasons I explained in the magazine, Eastport had worked up a booming business as the east coast shipping center for pregnant cows, which were en route to markets across the Atlantic, especially in Turkey. (Short explanation: Countries in Europe were looking to rebuild their cattle stock, with a preference for cows from the U.S. It was more efficient in various ways to send cows over while already pregnant, so the calves would be born in Europe.) We didn’t happen to be in town during one of the pregnant-cattle drives, but we heard about cowpokes from Texas guiding their herds into hay-filled containers that would be put on ships, and riding with them until they debarked on the other side.

When we visited the dock in Eastport last week, we saw the special cattle-containers stacked up—and empty. Why? Because of war in Syria and the related tumult in Turkey. Turkey had been the main customer for Eastport’s cows; violence and disorder in Syria spilled over the Turkish borders, including to major cattle areas; the Turkish buyers had put their orders on hold.

“We watch to see what the PKK is doing with ceasefires,” the port director Chris Gardner told me last week, when I had breakfast with him and Bob Peacock at the WaCo diner. He was referring to forces from the Kurdistan Workers Party who have been fighting in Turkey. “I can’t believe I’m sitting in little Eastport talking about the PKK, but that’s the reality,” he said.

2. Wood pellets. Some 90 percent of Maine is now covered by forest. That is a larger share than a century ago, when parts of the forest had been cleared for little farms and grazing areas. It may be more than at any other time in the state’s post-colonial-era history. There is a whole lot more to say on this theme—which I’m not going to say, and will instead refer you to this University of Maine report as a starting point. (Plus its Forest Bioproducts Research Institute, and its analyses of what climate change will mean for the state.)

Maine’s tree-based industries have been in a long decline—fewer mills, fewer loggers, fewer viable businesses based on growing, cutting, and processing trees. The three big commercial uses for trees are: making paper, building, and energy-production (burning). For a variety of reasons, the trends in all these areas have been down.

But then an anomaly of European “clean-energy” policy created a big market opportunity for “pelletized wood” from American forests. Short version: because trees can be regrown, ground-up wood counts as “renewable energy” biomass by European standards. EU policies require that renewable biomass make up at least 20 percent of EU energy supply by 2020; in practice, this means a big market for substituting wood pellets in place of coal in power plants.

There’s a complex debate on how much sense these rules actually make, from a global climate perspective. (You’re growing trees in the U.S., using the energy to cut and grind them and ship them all the way to Europe, so you can reduce the carbon footprint of burning coal?) Here’s one academic study on the overall benefits, plus another from the Forest Service. For now my point is: A regulatory decision by the European Union opened up a potential big new market for trees along the U.S. east coast, and Eastport made a big investment in port facilities to handle the shipments. Other sorts of wood-fiber markets in Europe and elsewhere, for fiber-board and related products, were opening up as well.

Meanwhile another global shift far beyond Eastport’s control has pushed in the opposite direction. The fracking-driven fall in world energy prices has also lowered the price for wood pellets, as it has for oil and everything else. (And to disrupt things further, a “wall of wood” is coming onto the market from commercial producers worldwide. This is a a whole separate topic you can start on here.) “If the price for fiber were even at the low-end of the pre-2008 [great recession] level, we would be fine,” Chris Gardner said. “And the exchange rate!”—a much stronger dollar versus the Euro, because of Euro-stagnation, Brexit, and other far-from-Eastport factors, makes Maine wood far more expensive for European customers.

The world economy giveth (to Eastport), in the form of E.U. biomass regulations; it taketh, in collapsing commodity prices plus currency changes; and it is certain to goeth in unpredictable new directions.

And meanwhile, the disruption in Syria and Turkey has also upset what had been a promising market for Maine-grown construction wood there.

3. Glossy paper in China. The docks in Eastport are still humming. Last week I saw trucks labor in and out every few minutes all day long, some 18,000 inbound loads each year, carrying bales of high-grade kraft pulp from the Maine woods. Last week longshoremen were loading these rapidly into a Liberian-registered ship with a mainly Filipino crew and a Ukrainian captain, bound for ports in Asia.

Why Asia? Although demand for many kinds of wood products is down, from newsprint (sigh!) to construction lumber, demand for the high-quality paper used for photo prints, glossy magazines, packaging, and other richer-country products is rising, especially in China as its prosperous-consumer class grows. “Is this going to be processed there and sent back here from China, as exports?” I asked Bob Peacock, when he was showing me around the dock. “No, it’s mostly for them,” he said.

Of course there is more to each of these industries, and more to the global forces affecting this little town. Recent ever-hotter summers have meant more summer vacationers looking for sites ever-further north. The record-snowy winter of 2014-2015 dumped 16 feet of snow on Eastport, which paralyzed it at just the time its downtown breakwater had collapsed. Its fisheries and aquaculture industries are parts of global markets—and ecosystems. And like everyone in Maine, people in Eastport are subject to the vagaries of the state’s erratic governor, Paul LePage.

For now the point is, the more closely you examine any part of the fabric of American life, the more you see its connections—good, bad, and merely complicated—with the rest of the world. You also see the opportunities that open for the well-prepared, and the changes that no preparations can offset. And you see the gulf between these complexities and the stark terms in which “the economy” and “great trade deals” are discussed during political campaigns.

“I guess I’ve learned to be careful what you wish for,” Chris Gardner told me at the WaCo. “It’s been a big part of our program to put Eastport on the map. We’ve done that—but one thing it means is that this place is much more at the whim of global trends and upheavals. As I said about the PKK, I guess I take a strange satisfaction that we are sitting here in eastern Maine and talking about how stuff on the other side of the world is going to affect us.”

He and his colleagues are upbeat people, and they remain optimistic about how they are positioned for the long run.