As we’ve traveled around the country with our American Futures and Our Towns projects since 2013, my husband, Jim, and I have evolved from being skeptics to evangelists about the impact of public arts on communities. We have seen how towns’ self-image, their presentation to visitors, their marking of history or current experience, their civic engagement and quality of everyday life and interactions of residents can all be changed by the public arts.

The array of art is created by everyone from professional artists to young children, bringing a rich collection of perspectives and making for opportunity for all to participate. Judgment seems to be more forgiving of arts that are public; sometimes the process of creation brings more value than the product.

It may be daunting for people to start public-arts projects: Who gets to decide? Is it worthy? Will it be expensive? And so on. But we have run across some that are imagined and executed in a very simple way. Here is one unusual example that surely qualifies as a Big Little Idea that any town could try and that has delivered a big payoff.

In 2011, Israel Centeno was living in Pittsburgh, in the neighborhood called the Mexican War Streets. It is a proud, eclectic neighborhood on the near north side of town, walking distance to a few of Pittsburgh’s bridges and the stadium, a park, and the riverfront, old warehouses in transition, and much more. Interesting people live in the neighborhood: young families who decorate their rowhouses at Halloween, creative types of all sorts, longtime residents, all of whom feel attached to their community.

In the middle of this is a small street called Sampsonia Way, which I would describe as an American version of a Beijing hutong. Attached houses, a dusty street that is not quite paved, and an intimacy among neighbors. Centeno lived with his wife and two daughters in a renovated rowhouse there.

Centeno is a writer and poet who needed asylum from his native Venezuela. He was offered sanctuary to live and work there for a few years by City of Asylum, an organization founded and originally funded by a Pittsburgh couple, Henry Reese and Diane Samuels, an entrepreneur and an artist.

City of Asylum is celebrating its 15th anniversary of offering asylum to exiled artists from countries like Iran, Burma, China, El Salvador, Iraq, and more. In exchange, the artists give back to Pittsburgh in the form of some kind of artistic work and public presentation. Several of the artists who have passed through City of Asylum are returning for that celebration. They will surely admire all the expansions that have happened since we first visited in 2014. There is a new park, called the Alphabet Reading Garden, also a newly renovated Masonic Temple building turned into a literary center for readings, a bookstore, a coffee shop, and performance spaces. Crowds for the artists’ public presentations have continued to grow.

Israel Centeno’s Big Little Idea is called the River of Words. Here’s how it worked:

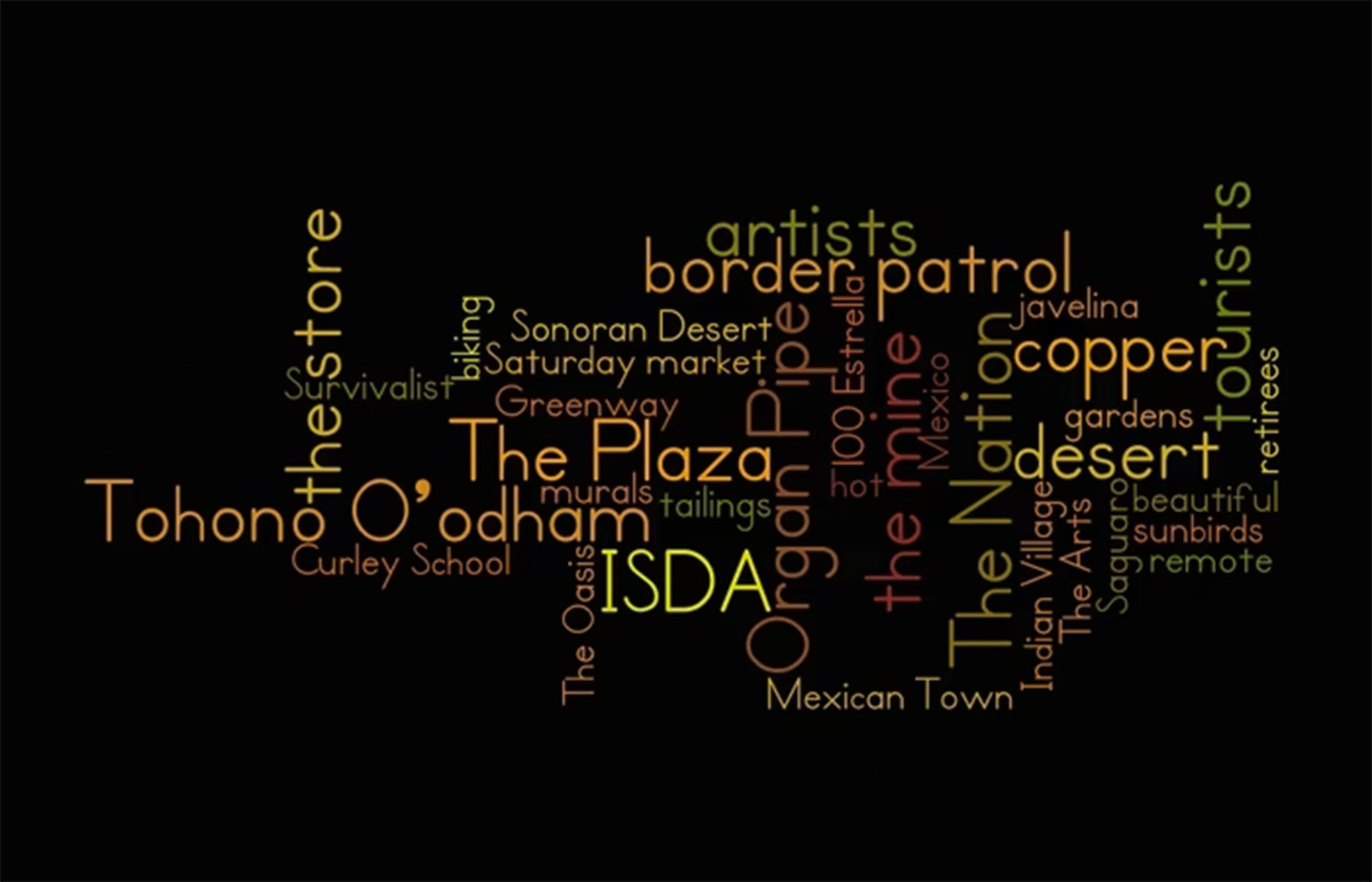

Centeno chose 100 words, which to him held some special meaning for Pittsburgh and his evolving experience there. Among them were all kinds of words: talent, thought, baseball, temperance, equation, horizon, ginger, nostalgia, fear, plenilunio, God. Then, the residents of the neighborhood were invited to adopt and host a “word in residence” and to display it for the public. The reaction was astonishing. People went crazy, in a good way, claiming their words. “Vortex! I must have vortex!” cried one.

A graphic artist, Carolina Arnal, and Gisela Romero, a graphic designer and visual artist, fabricated and affixed the words, from bold to lightly conspicuous, sometimes on a garden gate, by the front door, near a window.

What began as a temporary installation in 2014 remains, as residents refused to give up their words. Henry Reese told me that only a few are gone, and those because the owners moved and took the words with them. When Jim and I returned early on after the installations, we prowled around looking for the words, wondering each time we found one about the backstory of the word and the owners.

Now there is a map to follow for some of the words, which reminded me of the Map of the Stars near Hollywood.

Hosts of the words tell stories about the installations, and how curious neighbors came out of their houses to watch, and ended up asking for their own words to adopt. They talk about how the words help create an identity for the community and to share that story with anyone who happens by. Sometimes, I daresay, they puzzle, which makes people stop, think, and discuss.

We all know the power of words. They can please or hurt; indict or free; validate, disarm, declare, symbolize, obfuscate, or clarify. Sometimes they can’t be translated, so we borrow them from one language into another. Sometimes they are used incorrectly, out of ignorance or for effect. They can stand for much more than their size alone, especially single words, or short phrases. Their meanings can grow and shrink over time. Sometimes we make them up when we need them for inventions or marketing. Some catch on. Others go out of fashion or disappear. Their pronunciations change; their versions change within their grammars or social mores. Alphabets change. What have I overlooked?

River of Words may do all these things. It also marks a moment in time in the history of this community on the North Side of Pittsburgh, which is something the residents there seem to appreciate and acknowledge. That is a lot to say about 100 words.